Another measles outbreak: recognize measles in your child

A typical measles rash, courtesy of the public health library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

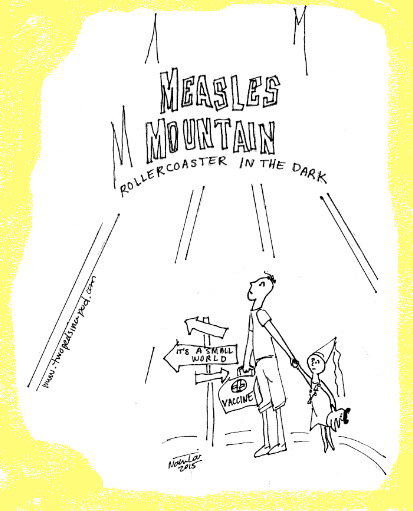

It saddens us that we need to post about how to recognize measles, but the recent measles outbreaks in the United States force parents to be vigilant for a disease that was nearly eradicated in this country.

Both an increase in international travel and a decrease in parents vaccinating their kids is thought to be responsible for the increase in measles cases.

Measles typically starts out looking like a really bad cold

— kids develop cough, runny nose, runny bloodshot eyes, fever, fatigue, and muscle aches.

Around the fourth day of illness, the fever spikes to 104 F or more and a red rash starts at the hairline and face and works its way down the body and out to arms and legs, as shown here at the Immunization Coalition site. Just before the rash, many kids develop Koplik spots on the inside of the mouth: small, slightly raised, bluish-white spots on a red base.

Call your child’s doctor if you suspect that your child has measles. Parents should be most suspicious if their children have not received MMR vaccine and were exposed to a definite case of measles or visited an area with known measles.

In the US, one in 10 kids with measles will develop an ear infection and one in 20 will develop pneumonia. Roughly one in 1000 kids develop permanent brain damage, and up to two in 1000 who get measles die from measles complications. Kids under age 5 years are the most vulnerable to complications. These statistics are found here. For global stats on measles, please see this World Health Organization page.

Check that your child is up to date on their MMR (measles) vaccine. The first dose is given between ages 12-15 months and the second dose is given at school entry, typically at 4-6 years of age. If you are traveling internationally with your baby between the ages of 6-12 months, ask your pediatrician about getting an early dose of vaccine.

Preventing measles is key because there is no cure.

Julie Kardos, MD and Naline Lai, MD

©2019 Two Peds in a Pod®